If you aren’t overtly political, then don’t let yourself get dragged into disruptive intra-team politics.

In motorsport that’s a must. And it would be a decent requiem for Erik Comas’ F1 career that spanned four seasons in the early 1990s and signed off a single-seater career that had looked to have all the glitz and potential of his great contemporary Jean Alesi.

Few reckoned Comas was as good as Alesi. But his record until F1 was just as good, if not better.

Some of his engineers, among them current FIA technical chief Vincent Gaillardot, recalled to The Race last year “a special talent who should have achieved much more in F1”.

The apolitical core within Comas undoubtedly didn’t help him – in fact, it patently went against his efforts on the track. But it was just who he was.

“He was a very strong but very non-political team-mate, he was definitely not political in any way, that was for sure,” recalls his 1990 DAMS F3000 team-mate Allan McNish.

“It just wasn’t in him to be like that. I really liked him, even though I knew I had to try and beat him in the same team.”

Managerless throughout his career, Comas ploughed his own furrow despite huge patriotic pressure from French state energy company Elf in his early career and into F1.

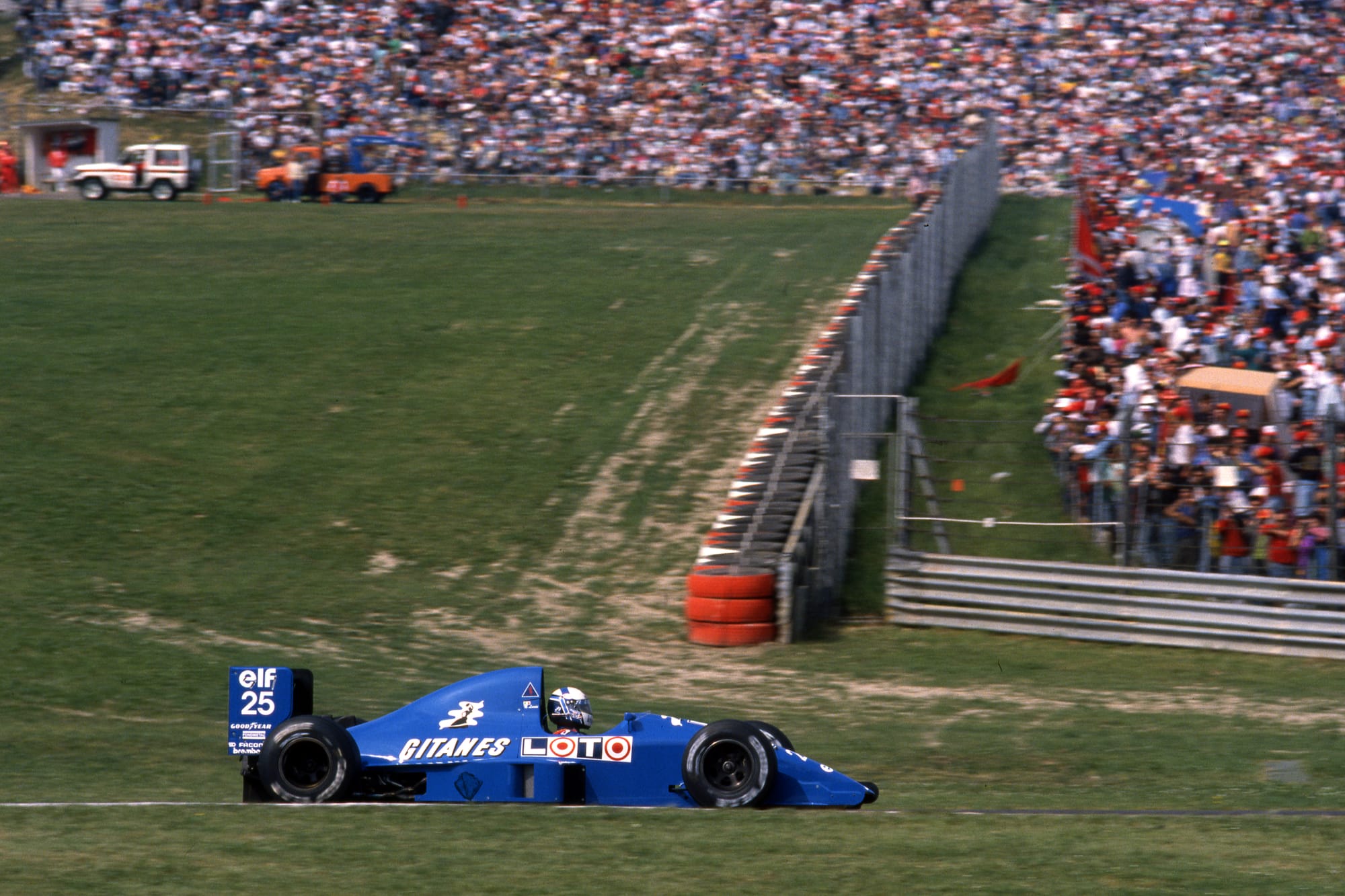

It was a set-up that probably undid his hard work and by the time he’d completed two seasons at Ligier in 1991 and 1992, he was already frazzled.

It damaged what should have been a long and distinguished grand prix career.

“I never had a manager in my life,” Comas recalled to The Race’s Sam Smith in a previously unpublished 2014 interview.

“It just didn’t happen. I was on my own, and it was probably a mistake.”

The Glorious Early Years

“I started one year after Alesi, but I was a year older than him,” recalls Comas.

“Jean was a tough racer. But clearly a talent and in 1987 I was really learning how to drive F3 cars after mainly racing in other things.”

Those other things gave Comas an almost unique scope of racing knowledge in the formative years of his career.

A Renault 5 Turbo champion in 1986 and a French Supertourisme (Touring Car) title winner a year later, Comas didn’t sit in a proper single-seater competitively until the end of 1986 in readiness for a full crack at a hugely competitive French F3 series in ’87.

That was with a specially-devised team under the state-backed fuel company Elf but with a recalcitrant Ralt chassis, while Alesi shone in a Dallara.

There was one huge positive for Comas though at the F1 grand prix support race at Paul Ricard in July, with watching F1 team bosses in attendance.

“I had really won the race from Jean, and I was in the position to win it. I was ahead and it was going to be the shock of the weekend but it was not to be,” remembers Comas.

He stumbled upon a backmarker and went off briefly, finishing third behind Alesi and his Ecurie Elf partner and future F3000 team-mate Eric Bernard.

A year later, racing for the renowned ORECA squad, Comas – now in a Dallara – beat Jean-Marc Gounon, Eric Cheli and Philippe Gache to the title, catching the eye of then-Ligier F1 driver Rene Arnoux.

The seven-time F1 race winner had just entered into a joint venture with oil executive Jean-Paul Driot, journalist Gilles Gaignault and computer distribution magnet Pierre Blanchet, known as GDBA, taking the first letter of each surname to create the clunky moniker.

When Driot and Arnoux created a more refined squad with DAMS for 1989, with major Elf backing attached, Comas joined Bernard who already had a season of F3000 under his belt with the factory Lola team.

For Comas it was a formative time and one that was fast-tracked beyond his own ambition and imagination.

“I never thought I’d be a professional driver, let alone an F1 driver,” he says modestly.

“It probably helped me because at the time when I was doing lots of different racing at a young age, I was fighting against [ex-F1 drivers] Jean-Pierre Jabouille and Jean-Pierre Jarier [in Supertourisme]. Big men.”

Comas’ first F3000 season was a triumph as he took a brace of late-season wins at Le Mans’ Bugatti circuit layout and Dijon to actually tie on points with champion Alesi, who had vacated his seat at the final race knowing he was champion (on countback at worst) to race in F1’s Japanese Grand Prix for Tyrrell – although a neck injury meant he wouldn’t start the race anyway.

Continuity was set for 1990 as the Driot-led DAMS squad added Marlboro to its portfolio of backers, bringing in a 19-year-old McNish as Comas’ team-mate.

“Before I joined, Erik was definitely the king of DAMS,” McNish told The Race.

“He was extremely quick at the beginning of the year and I would say a little bit more consistent than me in my first season. But he had a bit of a meltdown in the middle of the year and it didn’t quite go according to plan for a few races.

“I had a really strong run at Enna and then Brands Hatch where I won, yet he pulled it back together very well and won the title, so he ran out the easy winner in the end.”

1990 International Formula 3000

- Erik Comas – 51

- Eric van de Poele – 30

- Eddie Irvine – 27

- Allan McNish – 26

That meant Comas had taken four titles in four years, including one in one of Europe’s toughest F3 titles and another in the key springboard to F1. He was hot property, for a few months anyway…

Missed connection

When Nigel Mansell, amid a fit of paranoia – peaking over a supposed bout of Alain Prost politicking at Ferrari in the summer of 1990 – announced his retirement, a door for Comas became ajar for a possible debut in F1 via a top team.

With Alesi tying himself in knots with Ferrari, Williams and Tyrrell, Mansell seemingly heading for the golf course and Williams incumbent Thierry Boutsen already out of favour despite his Hungaroring win heroics, Comas was eyeing the possibility of joining Williams.

It came via some lobbying by Elf, and while it was only a fleeting possibility, Comas sees it now as a juncture in which his F1 dreams of glory were already fading.

When Mansell did a U-turn on his retirement announcement and signed with Williams, any chance of Comas getting a seat there vanished.

“Elf said ‘[as] it’s not possible, you cannot go to Williams, you have to go to Ligier for 1991’,” remembers Comas.

“I said, ‘you’re joking, Ligier has not scored a point in the last two years [it did score with both drivers in 1989, but only three in total] so I don’t want to go to Ligier’.

“Then Eddie Jordan called me and said, ‘Erik, come to my team in Formula 1 but I need $2 million, so I said to Elf that I need $2 million to go to Jordan, and it could be good.

“Then it was their turn to say, ‘you’re joking’ and the conversation was over.”

Jordan was the preference for Comas but “Elf was involved with Williams and Ligier only” he adds.

But after his recent successes, Comas was still in demand – with a previously unreported offer from an ambitious Jean Todt, then with the Peugeot world sportscar team.

“I went to see him [Todt] in Paris and he made me an offer,” he recalls.

“It was good but not F1, and then Renault and Elf said, ‘Erik, if you go there [to Peugeot] forget about F1, you will never drive a Renault engine or with Elf anymore’.

“So basically, I was stuck with Ligier.”

That was bad news for Comas because the team was in tumult. It had its joint worst-ever season in 1990 with zero points on the board amid a litany of wrecked tubs, mostly via the hands of Philippe Alliot.

When Comas arrived at the team for 1991 – with Boutsen alongside as his team-mate – there was little to suggest it was going to get out of its long slump and return to its late 70s and early 80s zenith.

“In winter testing it was OK and I was working with two good engineers, Claude Galopin and Richard Divila, and we were 0.8s quicker than Boutsen most of winter testing,” says Comas.

“But this car was also a disaster. That is the year that Ligier decided to make a big organisation change of the team and also take the Lamborghini engine.

“Guy [Ligier] said we are too much like a Formula 3000 team and that we need two technical directors. So, we moved from 100 to 180-200 people. That was a mess because we didn’t know who was doing what.

“I started to say that the centre of pressure of this new Ligier was wrong because the car had this long nose and in the high-speed corners the car was very light but when you needed a little bit of downforce on the braking on slow corners, we had no downforce.”

Comas, Divila and Galopin made some changes but, in typical Guy Ligier fashion, this created a maelstrom of ill-feeling and needless politics within the team, despite the changes being proven to be beneficial.

“Then Guy sacked my two engineers [Divila and Galopin],” remembers Comas.

“They put me with another engineer and it was a disaster. I knew from there it would not work in 1991.”

To the surprise of no one, Comas and Boutsen didn’t score a single point, as they faded into the lower-midfield (at best) abyss of a full 26-car grid.

The Ligier JS35B was overweight, needing a large oil tank to quench the thirst of the gloriously sounding Lambo V12. Neither Frank Dernie, recruited from Lotus in the spring of ’91, nor design legend Gerard Ducarouge couldn’t salvage anything from the season.

At Hockenheim, Comas at least brought Ligier some headlines when he got into a pit garage altercation with a furious Mansell in practice after an alleged baulking incident. Comas then completed a miserable weekend by rolling his car at the Ostkurve chicane.

“I was a big fan of Mansell, I loved the man who was driving but not the man who was shouting at me in my own garage,” recalls Comas.

“It was fantastic to watch him in action but the human side of the man is another story because he has a strange character, sometimes you cannot even talk about it.

“I was struggling to qualify and I had to drive at the limit, not considering who was behind because I was on a quick lap.

“I was not there to give him room but to save my life and qualify, which I did, just [making the race] in 26th, that lap was important and he was upset that I did not give him more room than he had.”

After a bruising introduction to F1, Comas was looking at the positives for ’92 when he knew that Dernie would deliver his first Ligier design and Renault V10 engines from the competitive Williams campaign of the previous year would be heading to Ligier’s base at Magny Cours.

But Ligier had other plans. It revolved around a bit of a pipe dream in the shape of then-triple world champion Alain Prost, who had just come on the market after his firey split with Ferrari.

“Because I was the cheapest to sack, Guy said ‘if one has to go because Prost is driving, that will be the cheapest one, so goodbye Comas’,” he recalls.

As Prost completed several tests while ruminating on whether Ligier had what it took to activate a renaissance, Comas was left high and dry, saying that “they didn’t let me drive any kilometres in the winter”.

He adds: “I never drove the Renault engine, never did I even get a seat made because Prost was convincing them that he will drive it because he did the winter tests.

“Then the week before the South African Grand Prix, Ligier called me and said: ‘Erik, fly to Kyalami because you race, Prost is not doing it!’

“I saw my seat [for the first time] in Kyalami, can you believe that? I was supposed to be the reserve driver and they didn’t even think about doing a seat at the factory, they were just treating me like s***. I was there because Elf had said ‘OK, this is your driver’.”

Comas described his qualifying run at Kyalami as “hell”, even though he somehow managed to line up 13th, marginally beating Boutsen in the other Renault-powered JS37.

He then embarked on statistically his best season in F1, taking a fifth at Magny-Cours and two sixth places at Montreal and Hockenheim. Qualifying was close, with Boutsen just winning out 8-6, while Comas’ four points outscored Boutsen’s two.

“All that year was a bit bad because it was not the career I had in mind for me as the Renault [engine] was good but the car was s***,” says Comas.

While the Ligier-Renault was dynamite on the straights, there was one very weak link in the package.

“We broke 78 gearboxes; the car was flexing and we broke the gearbox between the two driveshaft exits a lot,” Comas adds.

“At Magny-Cours in testing we actually took two wheels off, the rear wheels, with half of the gearbox and the rear wing, when something broke!”

Something else that flexed and fractured was Comas’ relationship with Boutsen. It was tipped to boiling point first at Interlagos – when the pair collided as Boutsen attempted an ambitious overtake, also wiping out an innocent Johnny Herbert in his Lotus.

Then there was another skirmish at the Hungaroring when Comas spun at the first corner and collected Boutsen. Herbert again was left seeing a familiar wall of blue, getting pitched into the gravel for the second time in a few months thanks to the squabbling pair.

Comas (above right) is now reflective of his relationship with Boutsen (above left), another mild-mannered and famously apolitical racer. Maybe it was a case of having too similar personalities, although Comas still has reservations.

“He was just coming from a two-year stint at Williams so he was clearly the top driver and I was the rookie,” says Comas.

“Ligier wanted to build up a political system with the drivers. I was not political and I never relied on the politics in a team. I was close with my engineer, even Renault, most of the time.

“They were my family that I was spending weeks and weeks with. But in F1 it does not work like this, spending time with the boys, having dinner, all the things I enjoyed in F3000, this is only one aspect.

“Thierry [pictured below] was at the end of his career and he had more experience of the political landscape. He saw in the winter of 90/91 that I was constantly running faster than him, so I think he wanted to protect his number one position, the political way.

“Even when we had the crash in Brazil early in ’92 he was immediately on the phone with [Guy] Ligier. The fact he was playing behind my back with me of course didn’t help to have a good relationship.

“He was a nice guy but it wasn’t a great working relationship because we were at two different ends of our careers.”

By the end of 1992, Comas was already looking elsewhere for drives, knowing that the structure of Ligier was creaking under Guy Ligier’s loss of interest and a ferment of political activity when the team was taken over, erroneously as it turned out, by former AGS stakeholder Cyril Bourlon de Rouvre, who was eventually jailed for fraud after the full debacle of the takeover became known.

“I was looking at the next era for myself then,” says Comas.

“Because I was really at the peak of my form of what I was doing, I was really doing the best I could but I was so tired of the system at Ligier. It was not the world I was used to.”

When a cultural change swept through Ligier, as de Rouvre walked through the door and then into a jail cell, Martin Brundle and Mark Blundell were hired, and Comas sought refuge at Larousse for 1993 and 1994.

It brought minimal results as the team struggled to raise sufficient budget, and as the team was swallowed up by the early and mid-nineties struggles, so too was Comas’ brief career at the pinnacle, which came to a tepid end.

The famous Senna incidents

Comas’ well decorated non-F1 career went on to include two All Japan Grand Touring Car Championship titles – the series now called Super GT – and eight Le Mans starts, including a second-place finish with Pescarolo Sport in 2005.

But his stamp on motorsport also includes two well-known incidents that involved Ayrton Senna.

The first came in morning practice for the 1992 Belgian Grand Prix when Comas comprehensively crashed his Ligier on the exit of the flat-out Blanchimont lefthander. Knocked out, with his right foot braced against the throttle and the Renault V10 screaming, it was clear he was in trouble.

“A few weeks before at the Spa 24 Hours the Touring Cars were going on two wheels because of the kerbs on the inside, so it was decided to remove the kerbs,” remembers Comas.

“They put them back for the grand prix [weekend] and on the third lap of free practice I was following JJ Lehto in the Dallara and he put the left wheels inside and sprayed gravel, I didn’t see it. I was doing 300kph and I went to the barrier big time.”

A following Senna stopped his car beyond the shunt scene and sprinted back to the wrecked Ligier.

Seeing the prostrate driver, Senna reached inside the cockpit and turned the engine off before supporting Comas’ head until the medical teams arrived. It was the incident in which Professor Sid Watkins called Senna ‘a good pupil’ after their long friendship developed.

“I can’t remember lots,” adds Comas. “But thanks to Ayrton, what he did was very brave.

“He is the only one that stopped his car and came. I was at full rpm with a car that was destroyed, water leak, oil leak and a full tank of gas.

“So, the car was a potential bomb and the fact that he came and switched off the main switch that the marshal could not find, maybe he saved my life that day.

“When I came to Formula 1 [in 1991], Senna came to congratulate me about the Formula 3000 title in 1990.

“And from that day I could say Senna was a friend. OK, not a close friend or anything. I was always shy because he was a legend already, and I was a beginner in F1 at that time, but we spoke sometimes.”

In a dreadful reversal of the Spa incident, 18 months later at Imola on May 1, 1994, Comas came to witness Senna’s last moments up close after an awful error by pitlane officials.

As Senna lay at the side of the track, his terminal head injury being tended to by Professor Sid Watkins and the medical teams, and with the awaiting emergency helicopter on the track, unfathomably Comas was allowed to venture onto the track in his Larousse.

Going up through the gears to Tamburello, Comas was shocked to see the helicopter and medical services blocking the track. It perhaps remains one of the most bizarre and dangerous safety breaches in F1 history.

A commentating John Watson for Eurosport described Comas’ arrival to the scene as “gobsmacking” and “the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever seen at any time in my life”.

Comas braked before he got close to the helicopter but then had to watch the final desperate attempts to save Senna from his Larousse cockpit.

“I was in the pits and they released me by mistake, which they really should not have done, and to me this was just kind of destiny now,” says Comas.

“He [Senna] was there to save my life in 1992 and somehow I was there to see him going away. Seeing that scene for me was such a big shock.

“Why was I destined to be there?”

A deeply shocked Comas withdrew from the race, leaving the circuit quickly, being among the first to realise the severity of the situation that there was no hope for Senna.

“When I left this horrible scene I knew that it would be over for him,” Comas says.

“For 10 days I decided not to drive, but I got calls from the team who said ‘please drive the car once and then you decide’ but ‘please don’t stop like this’.

He went to Paul Ricard on the Tuesday before the next grand prix, in Monaco, and thought “maybe I will finish the season”.

Remarkably, Comas was eighth in first practice at Monaco and qualified his Larousse mid-grid despite still being in shock over the events of Imola.

But really it was the beginning of the end for Comas in F1, and by the end of 1994, he had decided to move on. Now with the benefit of time, there is some perspective.

“I was too patriotic at the time wishing that I could do my whole career with a French team,” he says in summary of his F1 career.

“Of course, up to F1 it was good for me but in F1 itself that was a mistake, a huge mistake.

“Eddie [Jordan] wanted me to join his team and maybe if things had been different that would have been amazing for me but I didn’t have two million dollars.

“I wish I’d driven that Jordan that [Michael] Schumacher made his debut with because that was an incredible car and it might all have been a different story. Who knows?

“I cannot regret it because I had to go in the direction that was offered by Elf.

“I mean, I’ve been enjoying my life being a professional, so to do what I always dreamed of is cool.

“I cannot have any regrets.”

Images courtesy of XPB/Jakob Ebrey Photography/GrandPrixPhoto.com